Aircraft makers feared the coronavirus pandemic would deal them and the buyers of their jets, the airlines and leasing groups, a near-mortal blow. Eighteen months on, passengers have returned — but mostly on short-haul routes.

As passenger demand nears or even matches pre-pandemic levels on shorter journeys where smaller, single-aisle jets are used, long-haul traffic remains subdued with many of the big wide-body planes that fly the intercontinental routes still sitting idle.

With more than 1,400 of these twin-aisle jets still in storage in aircraft hangars at the start of December, according to data from aviation consultancy Cirium, the timing of a recovery in the wide-body market remains uncertain.

Although the numbers are down from the peak of the pandemic in March 2020 when about 3,586 twin-aisles were in storage, it is still almost 30 per cent of the current fleet as airlines have been slow to bring these planes back into service.

It is a sharp contrast to pre-pandemic times when some executives say there were too many larger aircraft after a decade of strong production and deliveries.

When Covid hit, there was a “slightly inflated backlog of wide-body aeroplanes” after “a little bit of an order frenzy”, said Christian Scherer, chief commercial officer at Airbus.

The pandemic has helped to “sober that up” and “vaccinated the large airlines a little bit away from the big aircraft and a little bit more towards the lower risk, lower trip cost models”, he added.

In the run-up to the crisis, Boeing and Airbus were keen to push their big wide-body jets.

There was a “lot of excitement about the Boeing 787 and Airbus A350 [both wide-bodies] bringing a lot of technology and effective economics into the market”, said Kevin Michaels, managing director of Michigan-based AeroDynamic Advisory.

“It had been a period [the past decade] of robust air travel growth. We grew at this breakneck pace, and you had this curious high cost of fuel with low cost of capital. Putting those two together with new technology and a period of robust growth . . . all of those things conspired for airlines to order aggressively,” he added.

Scherer, however, is “absolutely convinced” market demand will resume for twin-aisle jets “with just as much a vengeance” as the market for short-range or domestic flying, once international and intercontinental traffic resumes.

But it may be “sometime between 2023 and 2025 barring anything else” before long-haul journeys recover, he said. It will then take longer still to return to pre-pandemic levels of production for the wide-body planes.

Other industry executives insist a recovery for long-haul and the wide-body market will happen, but admit it will be bumpy.

Warren East, chief executive of UK aero-engine maker Rolls-Royce, which is heavily exposed to the wide-body market, said in early December that any recovery would not be linear, especially in light of the Omicron variant. “It will be a story of 10 steps forward and two steps backwards,” he said.

Ed Bastian, Delta chief executive, echoed East’s comments, warning that Omicron had hit bookings in January, largely for international travel. The dip shows up “wherever . . . countries have put up travel restrictions”, he added.

Ihssane Mounir, Boeing’s senior vice-president of commercial sales, said “people do want to travel” and stressed that demand remained strong in the long-term. However, he admitted that it was “too early to call” when the manufacturer’s production rate for the 787, which peaked at 14 a month in 2019, would reach that height again.

“We’ve got to build up from two to five, then see how it goes,” he said.

Scherer’s view that the recovery in production rates for wide-body jets will take until the middle of the decade, at least, is shared by independent analysts.

“I believe production rates for new wide-bodies will not return to pre-pandemic levels, at least not for many years,” said Scott Hamilton, of aerospace consultancy Leeham News.

AeroDynamic’s Michaels agreed, saying it could be the 2030s before production rates for the twin-engined 787 hit 2019’s monthly peak of 14.

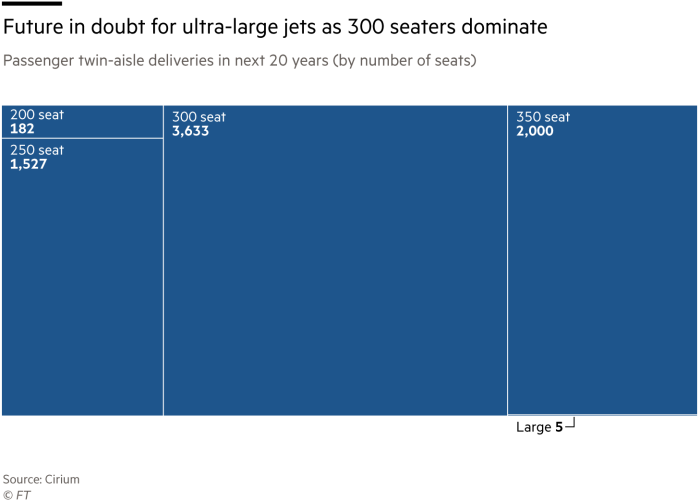

For the biggest jets, the four-engine planes, the market has “almost completely gone”, said Rob Morris, head of consultancy at Ascend by Cirium. “Many of those are getting parted-out or scrapped.”

There are green shoots, however, for the new twin-engined jets, according to John Plueger, chief executive of Air Lease, one of the world’s biggest aircraft lessors. “We are seeing a slow increase in demand for the new generation wide-bodies, but it is certainly not nearly as strong as the single-aisle.”

Demand for freight capacity is among the reasons for the uptick in wide-body demand, he said, as airlines use passenger aircraft to try to capitalise on high cargo and freight rates.

Predicting demand, however, has been complicated by Boeing’s protracted production problems with the 787 Dreamliner as it struggles to rectify quality issues. American Airlines said it would have to rejig its summer schedules because promised 787s had not arrived.

Plueger, another Dreamliner customer who cancelled three orders due to the problems, is visibly frustrated by the delays, saying: “We as an industry cannot be in a place . . . where one of the two airframe manufacturers simply cannot deliver one of its key products . . . The industry needs these aircraft and we need at least two strong main competitors in Boeing and Airbus.”

Boeing also has a big bet on a resurgence in international flying with its next wide-body model, the 777X. Offered in two variants, the 777-8 and 777-9, which can carry up to 426 passengers on long-haul routes, it is the biggest of the big now that the Airbus A380 has stopped production. The 777 has begun trials, but is running at least two years behind schedule.

Some observers think it will prove too large to appeal to the pandemic-seared airline audience.

“The 777-9 is simply too big for most airlines — it’s the next A380 and 747 in terms of being the wrong size in today’s market,” Hamilton, of Leeham News, said.

Others, however, think people should not count out the 777-900 wide-body jets. Michaels said Boeing will find customers among the big intercontinental Middle Eastern airlines. He expects Boeing to come out with a 777X freighter, too.

The 777X will be the biggest jet in the market when carriers begin replacing their largest aircraft in 2025 and 2026, Boeing’s Mounir said. With more than 300 orders for the aircraft already, “it’s time is definitely coming”, he added.

Despite the uncertainty in the timing of a recovery for the wide-body market, there is a large bright spot for the industry: demand has returned for single-aisle aircraft, with airlines clamouring to renew their fleets after the crisis.

Airbus’ Scherer said demand has remained firm despite the rise of the new Omicron variant. The airline community at large, he said, has realised that “when people can travel, they will travel and they will do so with a vengeance”.

Aerospace chiefs prepare for bumpy ride in recovery of long-haul flights

Pinoy Variant