US officials will sit down with Russian diplomats in Geneva on Monday in the first of a sequence of meetings that could prove crucial to European security.

Russia has laid out its red lines in two draft treaties — and with about 100,000 troops amassed close to Ukraine’s eastern border, has threatened military action if they are not met. US and European officials will counter with their own demands that Moscow abide by the fundamental principles of European security: that countries can decide their own foreign and defence policy and that borders are not changed by force.

Expectations of an agreement on a new security arrangement between Moscow and the west are low.

“I don’t think we’re going to see any breakthroughs next week,” Antony Blinken, US secretary of state, said on Sunday. “We’ll see if there are grounds for progress, [but] it’s very hard to see that happening when there’s an ongoing escalation, when Russia has a gun to the head of Ukraine.”

In Geneva Wendy Sherman, Blinken’s deputy, will try to stake out some common ground with her Russian counterpart Sergei Ryabkov that could pave the way to further talks.

“At this stage it is very much a dialogue, not a negotiation,” said one western official.

But Ryabkov said Moscow expected a “high probability” that the US and Nato would not take its demands seriously. “We won’t make any concessions under pressure or the threats western participants are constantly making at us,” Ryabkov told state newswire RIA Novosti.

The non-starters

Ryabkov said talks that did not take Russia’s demands as a starting point would be “pointless” and insisted Moscow would only negotiate on its own terms.

“We’re not going with our hands out, we’ve got a clearly defined goal that we need to achieve on the conditions we set. That’s all there is to it,” Ryabkov said.

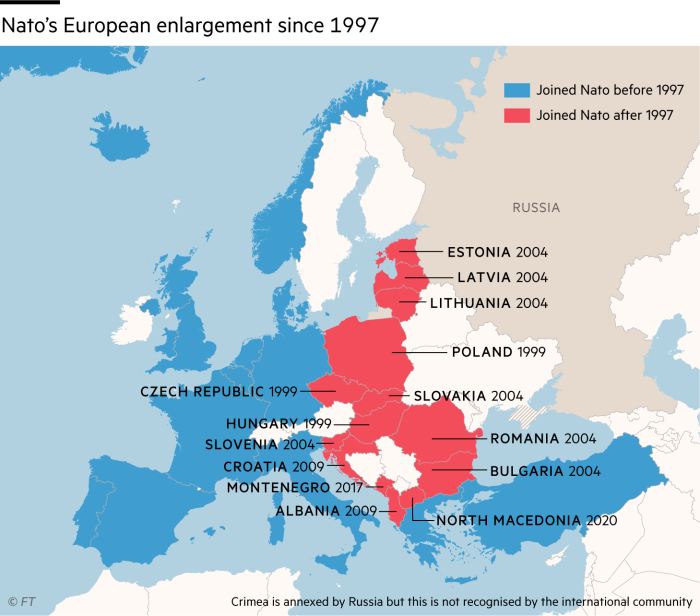

But Moscow’s top demand that there is no further enlargement of Nato has been firmly rejected by Washington and its allies.

“I don’t see either Nato or the US wanting to scratch that Russian itch,” said Rose Gottemoeller, a former Nato deputy secretary-general and ex-assistant US secretary of state for arms control. “Nato is not going to change its policy on enlargement, period. It is part of Nato’s DNA.”

Andrew Weiss, vice-president at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, said a deal akin to the Yalta agreements between the Soviet Union, US and UK that divided Europe after the second world war was unlikely,

Apart from former US president Donald Trump “it is just hard to imagine the willingness for a normal mainstream American politician to entertain moves with the Russians that bring back horrible memories of Yalta and other backroom dealings in the 19th century that caused immense hardship for countries in Europe”, he said.

A second Russian demand — that Nato powers do not deploy forces or weaponry in member states that joined after the fall of the Soviet Union — will also be rebuffed. Jens Stoltenberg, Nato secretary-general, said on Friday it would consign the alliance’s eastern members to second-class membership.

In 1997 Nato agreed not to permanently station combat forces in its members that had been part of the Soviet bloc and deployed very few troops or equipment in those countries.

The policy changed after Russia’s annexation of Crimea from Ukraine in 2014. Nato has beefed up its presence in Poland and the Baltic states. But the battle groups are small and posted on a rotational basis. It could in theory scale them back again but is unlikely to do so without a full Russian retreat from Ukraine.

Possible common ground

Russia’s call for a bar on the deployment of ground-launched intermediate range missiles could provide a basis for re-engagement on arms control. The 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty covering such weapons, which collapsed in 2019 over allegations of Russia violations, was breached when Moscow deployed its 9M729 cruise missile. The US might be prepared to renegotiate new controls if Russia agreed to include the 9M729 with verification mechanisms.

Moscow’s demands for restrictions on military deployments and on exercises close to its frontiers could be broached in a renegotiation of the Treaty of Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE), which Russia abandoned in 2015.

Lastly, Russia’s request for more transparency, consultation and exchanges with the alliance on security threats could be met through renewed use of existing procedures, known as the Vienna Documents, which Moscow has largely neglected.

Russia’s three meetings this week could theoretically pave the way to separate negotiations: with the US on arms control, with Nato on force deployment and exercises, and with the OSCE on transparency.

Despite scepticism about Russia’s serial violations, the west should be prepared to renegotiate security treaties, said Patricia Lewis, director of the international security programme at UK think-tank Chatham House.

“You can go into this in good faith — with your eyes wide open.”

The road ahead

A successful outcome of this week’s meetings would be a commitment by both sides to a “process and clear substantive agenda” for further talks, said Gottemoeller, but would require Moscow to seek “mutual benefit”.

Progress would also depend on Russian de-escalation at Ukraine’s borders. Blinken said Russian aggression against Ukraine would be “front and centre” in the meetings, but he indicated Monday’s session would not directly address the so-called Minsk process for ending the conflict in the eastern Donbas region, which is being steered by Paris and Berlin.

The big question, say analysts, is whether the Kremlin wants the talks to fail from the outset.

“Not only are they asking for things that you know for a fact are non-starters, they’re asking them specifically in a way that they know will ensure they won’t get them,” said Michael Kofman, senior research scientist at CNA, a Washington-based think-tank.

“The framing, even of the things in the Russian proposal that are plausible to discuss, is so inflammatory as to make it impossible,” said Samuel Charap, senior political scientist at the Rand Corporation, a US think-tank. “This is really about whether they’re willing to climb down from the maximalist demands and accept something less than the entire [set].”

West treads narrow path to common ground in Russia talks

Pinoy Variant